I don’t know why I’ve been thinking so much about the passage of time lately. There’s no good reason (or at least, no single reason) for it. I just get on philosophical jags now and again, and recently I’ve been paying attention to the way that I experience and think about time.

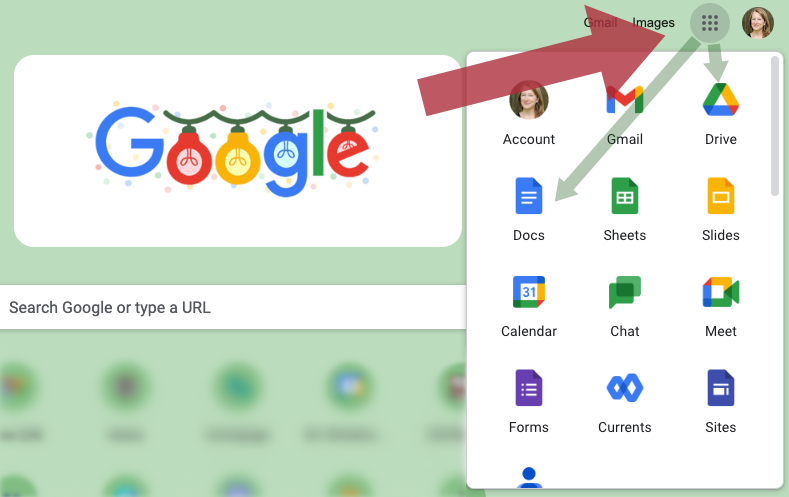

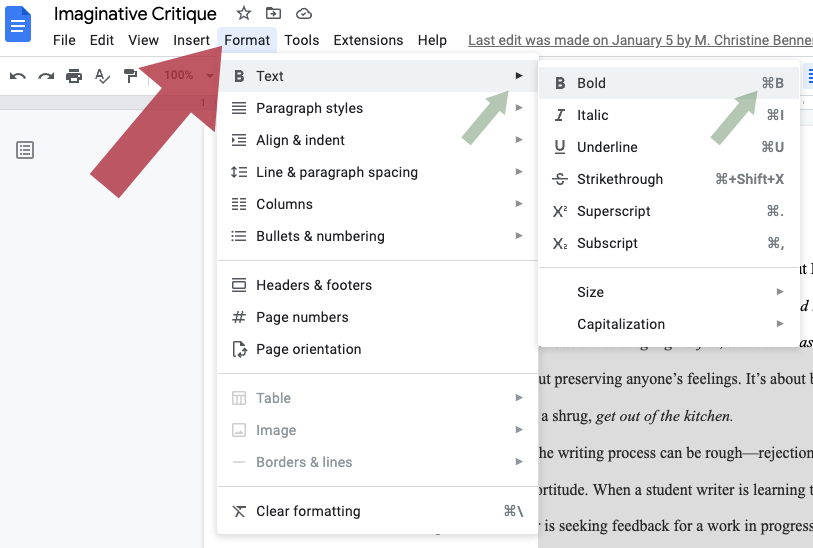

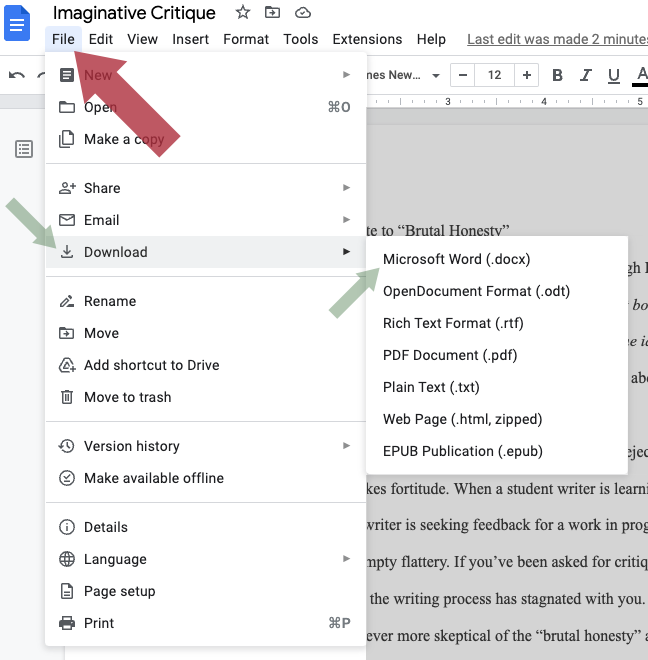

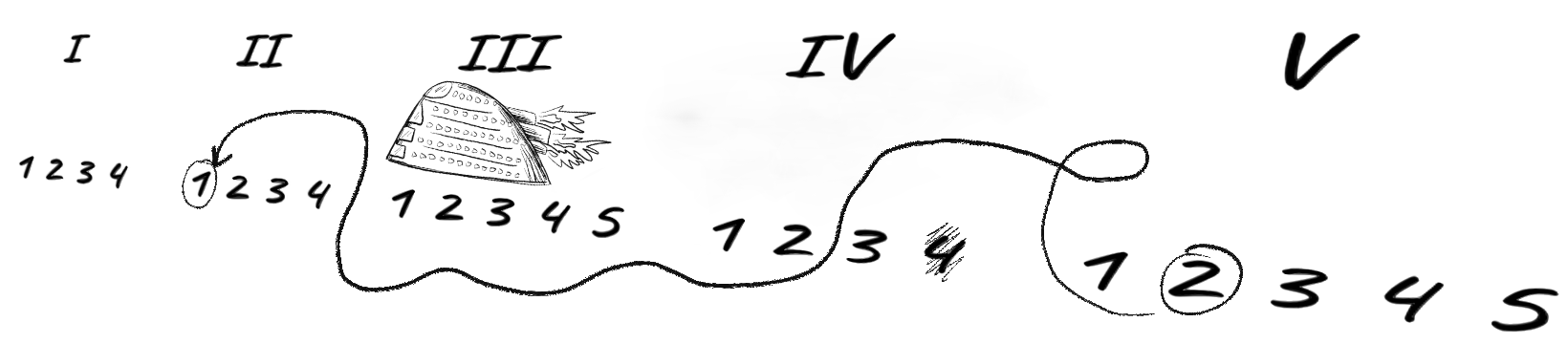

It could have something to do with my novel-in-progress. The timeline is anything but linear. A few folks who read an earlier draft very politely noted that they sometimes got lost in the chronology of the story. So now each scene in the manuscript has a little illustrated chart showing where we’ve been and where we’re going:

Did I mention that this is a space story? That little gumdrop-beehive-looking-thing with flames shooting out the back is the spaceship that hauls my characters around. (Don’t laugh. If the Borg can fly a giant cube through space, I can have the Gumdrop.)

This visual aid may not make it into the published version of the novel—heck, I haven’t even started shopping this manuscript around, so “published version” is still something of a pipe dream. But the illustration amuses me, and it helps make literal a rather circuitous path I take through time.

As chaotic as it may appear, it makes sense to me to write a story this way. I have a gumdrop-like relationship to time. One minute I’m in 2024, living one day after the next—the next I’m back thirty years riding the bus to middle school. So that’s how I tell my stories.

That said, it does help to have the first-one-thing-then-another chronology written down somewhere. For my space story, I have a detailed chronology of the events (with everyone’s relative ages) in a spreadsheet. For a different project (also a novel, but this one set on Earth, so no flying gumdrops), I recently finished a 39-page, 16,000-word outline detailing the this-then-that events of the story.

This outline traces all the major life events of a family over decades. But I promise you, that’s not how the story is going to come out. Mid-wedding, someone will inevitably tell a story about when they were all kids together. As one character anticipates her career-making trip to Washington, another will still be mulling over a fight with her brother that took place the month before.

The outline is a necessary tool, but it is not a roadmap. So help me, if you try to force me to write the story in order, you will have a rebellion on your hands.

The foldable, moldable nature of time allows me to tell stories in which people themselves are not linear. Everyone knows that that paragon of writerly achievement, character development, is not a straight line. Even if Hildegard begins the story believing she is doomed to failure and ends the story with a newfound trust in herself, she still carries her erstwhile doubts with her into her period of growth. She regresses, even as she learns. She doesn’t know how to move on and forget the past, because no one really does.

That’s the kind of story I like to tell. That’s the kind of story I can’t help telling. As long as someone out there wants to read that kind of story, I’ll be all set.

This post was first published in the newsletter of M.C. Benner Dixon.